How is location taken into account in nature reporting?

In the race to integrate biodiversity into business and investment decisions, location matters. Understanding where your organisation or portfolio intersects with ecosystems is not only a growing regulatory expectation — it's a necessary step toward credible and actionable nature strategies. Here's why, despite the complexity, it's worth getting right.

Why it’s critical to locate your interface with Nature

When measuring a carbon footprint, you can often rely on aggregated data as emissions are fungible: 1 tonne of CO₂ emitted in Australia has the same effect on the climate as 1 tonne emitted in France. But biodiversity is inherently local.

Your company’s impacts and dependencies on nature — and therefore its risks and opportunities — are tightly linked to place. Once again, a soy farm in Brazil and a tomato farm in Provence may both emit CO₂, but only one might threaten an endangered species or a critical wetland.

As a result, in biodiversity assessments, we must trace impacts to their physical origin: the forest cleared, the watershed tapped, the field sprayed. Nature pressures must be spatialised: it matters where land is used, where pollutants end up, and where species are displaced.

That’s why leading nature frameworks like TNFD, CSRD, and SBTN all place strong emphasis on identifying and prioritising nature interfaces based on location-specific context.

Why it’s complex

Locating your interface with nature is essential — but far from easy. The process requires handling complex, fragmented, and often unavailable data. Here’s why:

First, the data is multi-dimensional and scarce:

Biodiversity assessments must account for the 5 key pressures defined by IPBES: land use, climate change, pollution, invasive species, and resource exploitation. Each of these requires specific spatial datasets (e.g., deforestation risk maps, water stress layers), making the analysis both technically dense and data-hungry.

Moreover, value chains are often opaque and global. Pressures may occur well beyond direct operations — upstream or downstream, across jurisdictions, and with vastly different data standards. Mapping biodiversity impacts means linking pressures to specific geographies, which is particularly difficult without consistent traceability data. Provenance data is rarely available beyond Tier 1 suppliers. Tracing raw materials to their origin — whether a farm, a mine, or a field — is still a major bottleneck for most companies and financial institutions.

Second, existing tools are typically not fit for purpose:

Traditional GIS tools are powerful but slow and technical, which makes them poorly suited for non-experts.

They often require manual cross-analysis of dozens of spatial layers, lack automation for value chain-level assessments, and frequently fail to integrate biodiversity-specific datasets.

In short, they produce fragmented insights rather than a coherent view of nature-related risks and impacts.

Allocate your efforts where it matters: what leading frameworks recommend

The leading nature frameworks are asking businesses to assess dependencies, sensitivities, and impacts across their assets and identify high-priority areas for action. The idea is to identify both sensitive locations and material locations.

TNFD LEAP Framework

The LEAP framework from TNFD provides the clearest guidance on how to locate your interface with nature. The "L" phase — Locate — is designed to help organisations filter and prioritise where nature-related issues are likely to arise.

The L Phase step breakdown

L1. Span of the business model and value chain: identify activities by sector, value chain, and geography. Where are direct operations and key upstream/downstream nodes?

L2. Dependency and impact screening: which sectors and locations have moderate to high nature-related dependencies or impacts? -> What/where are your “material” sites?

L3. Interface with nature: map locations where dependencies/impacts intersect with ecosystems or biomes (e.g. mangroves, coral reefs, peatlands).

L4. Interface with sensitive areas:

- Prioritise activities that are physically located in or near ecologically sensitive areas. -> What/where are your “sensitive sites'“?

- Sensitive locations are defined by the presence of one or more of the following criteria:

1. Areas important for biodiversity, including species (= regions that are crucial for the survival of various species)

2. Areas of high ecosystem integrity (= ecosystems that are relatively undisturbed and function naturally)

3. Areas of rapid decline in ecosystem integrity (= regions where ecosystems are deteriorating quickly due to factors like deforestation)

4. Areas of high physical water risks (= locations facing significant water-related challenges)

5. Areas important for ecosystem service provision, including benefits to Indigenous Peoples, Local Communities, and stakeholders (= zones that provide essential services like pollination).

TNFD is recommending using some datasets to assist in identifying sensitive locations: World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs), Ramsar sites, UNESCO biosphere reserves, Natura 2000 sites and other zones of recognised ecological importance. Those reference datasets are given as an example, sensitive locations are not defined specifically by reference to a dataset.

The CSRD ESRS E4

The CSRD, via the ESRS E4 standard, goes one step further by requiring disclosure of:

The number and area of sites in or near biodiversity-sensitive areas;

The nature of activities taking place in those areas;

The actions taken to reduce pressure or restore ecosystems.

CSRD defines specifically what should be considered "biodiversity-sensitive area":

Biodiversity sensitive areas are Natura 2000 network of protected sites, UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA), as well as other protected areas recognised nationally or internationally.

The Science-Based Targets for Nature (SBTN)

The SBTN framework also requires companies to:

Map their interface with nature based on materiality (pressure × exposure) in Step 1.

Prioritise locations for target setting and action, especially where pressures are high and in protected & sensitive ecosystems, in Step 2.

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)

Under the SFDR, the Principal Adverse Impact (PAI) indicator no. 7 specifically addresses biodiversity risks — and requires a certain level of spatial understanding to assess exposure.

The PAI no 7 requires financial institutions to identify whether their portfolio companies have sites or operations that are located in or near biodiversity-sensitive areas. The SFDR does not define this term with full precision in the regulation itself, but associated guidance point to accepted biodiversity mapping standards, in line with other EU frameworks like the CSRD.

Overall, the four frameworks broadly align on the importance of localisation — with minor differences in how strictly they define “sensitive areas”.

How darwin helps you locate and assess

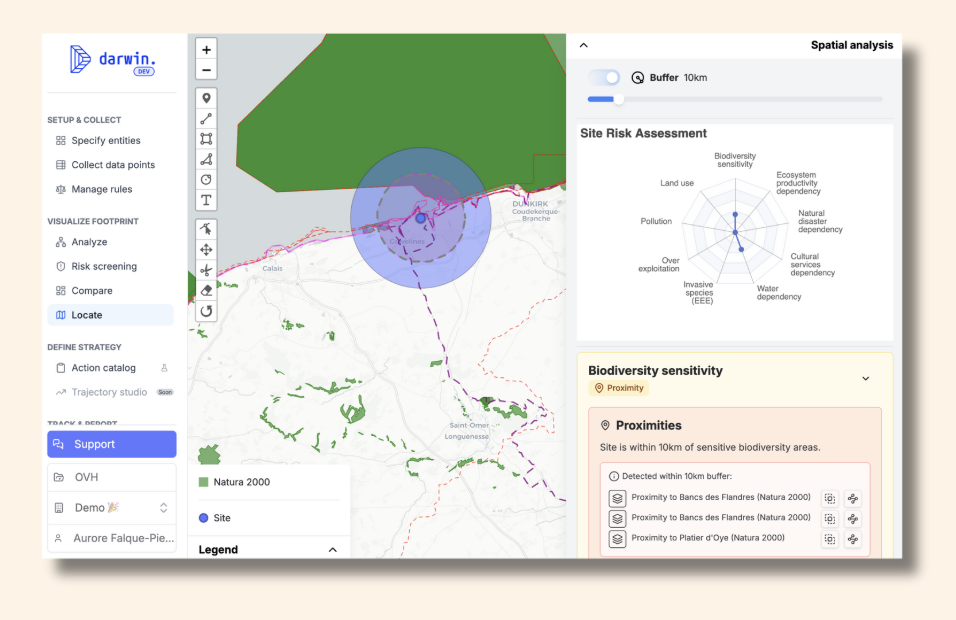

At darwin, we’ve built a platform that allows corporates and financial institutions to rapidly locate, map, and assess their interfaces with nature — whether through direct operations or value chains.

What makes our spatial analysis module unique:

It links site-level geospatial data (i.e. is this site located in a sensitive area? Is this site “sensitive”?) with granular footprint data (i.e. is this site important for us? is this site “material”?). It basically allows you to conduct the Locate and Assess phases of LEAP in parallel.

You can overlay thousands of assets or supplier locations with over 50 global nature related layers, covering state of nature, protected areas, major pressures, physical risks and so on.

Whether you're preparing a CSRD disclosure, setting targets via SBTN, or building a nature strategy aligned with TNFD, darwin enables you to ground your approach in spatial reality — where it matters most. We integrated spatial data at every project stage, from materiality assessments to site-level analysis.