Nature risks: beyond sites, beyond carbon.

Written in collaboration with PwC.

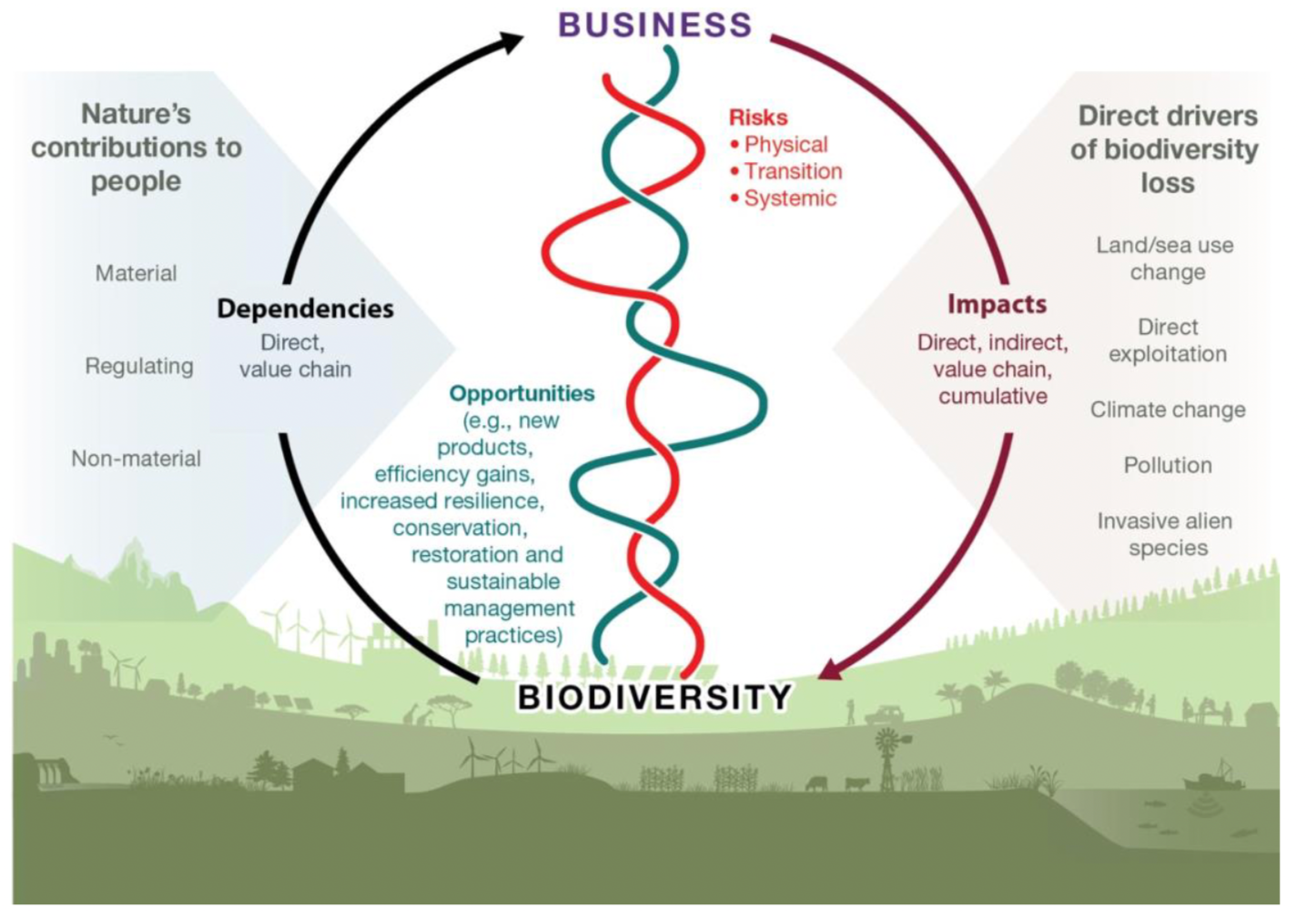

For years, environmental risk has largely been approached through a narrow lens: carbon, climate, and when nature risk was concerned often at the site level. But nature-related risks go far beyond GHG emissions or isolated assets. They are systemic, interconnected, and deeply embedded across value chains.

Understanding nature risks requires moving beyond static assessments and embracing a more comprehensive, forward-looking approach — one that captures dependencies, impacts, financial exposure and future shocks, but also opportunities.

1. Setting the scene: what do we mean by “nature risks”?

Nature risks are related to the exposure of economic activities to the degradation of natural systems and to the societal responses that follow. A robust view of nature risk must therefore be 360°, covering soil health, deforestation, pollution, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem disruption.

A useful distinction is between physical risks and transition risks.

Physical risks: dependencies on ecosystem services

Physical risks arise from dependencies on ecosystem services (= the free benefits that nature provides to economic activities). These services generally fall into three categories:

Provisioning services (e.g. timber, water, minerals),

Regulating and maintenance services (e.g. pollination, water regulation, climate regulation),

Cultural services (e.g. tourism, landscapes such as coral reefs).

When natural systems are degraded, their capacity to deliver these services declines, directly threatening business continuity. According to the European Central Bank, 72% of European companies are highly dependent on biodiversity, making this a systemic issue rather than a niche concern.

For instance, one example taken out of PwC client portfolio: in the telecom sector, companies depend heavily on critical minerals for electronic components. Lithium demand is expected to increase 13-fold between 2021 and 2040 (IEA). This creates a clear nature-related physical risk: supply constraints, cost inflation, and potential disruptions for companies reliant on these materials.

Transition risks: impacts on nature

Transition risks stem from how companies impact biodiversity and ecosystems, and how society reacts to these impacts.

As awareness of biodiversity loss increases, companies face:

stricter regulation (e.g. EUDR which now introduces stringent traceability and due-diligence requirements for commodities associated with deforestation),

market pressure from investors and customers,

societal pressure, including activism and reputational risks. Think of the debate over large infrastructure projects such as the A69 motorway in France, which illustrates how biodiversity concerns can translate into social opposition, legal challenges, and significant project delays.

In this context, a company’s impact on nature becomes a proxy for its exposure to future transition risks.

2. Measuring exposure to nature risks

Exposure captures how sensitive an activity is to nature-related risks.

Exposure to physical risks

It depends on the level of dependency on ecosystem services and the presence of operations or suppliers in sensitive areas.

Example: a software company may appear has having no dependencies to nature. Yet its reliance on data centres creates strong upstream dependencies on water availability. If these data centres are located in water-stressed regions, this dependency becomes a material physical risk.

Exposure to transition risks

It depends on the scale and typology of impacts on nature, and the regulatory, market and societal context.

Example: a European food manufacturer sourcing cocoa or coffee may now be exposed to a clear transition / compliance risk under the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). If suppliers cannot provide compliant traceability and geolocation evidence proving the commodities are deforestation-free, the company may face import bans, product withdrawals, fines, and supply-chain disruption.

From gross risk to net risk

While gross risk reflects inherent exposure, net risks consider vulnerability in their analysis.

Vulnerability is defined in the LEAP approach by:

The probability of the risk occurring (often hard to project for biodiversity),

The organisation’s capacity to mitigate or adapt.

3. From theory to practice: what does this look like in reality?

Darwin’s approach to nature risk

At Darwin, nature risk analysis is structured around 4 complementary lenses:

Sourcing analysis

Identification of priority sites

Assessment of financial exposure to nature risks

Estimation of potential future financial losses through a Nature Stress Test.

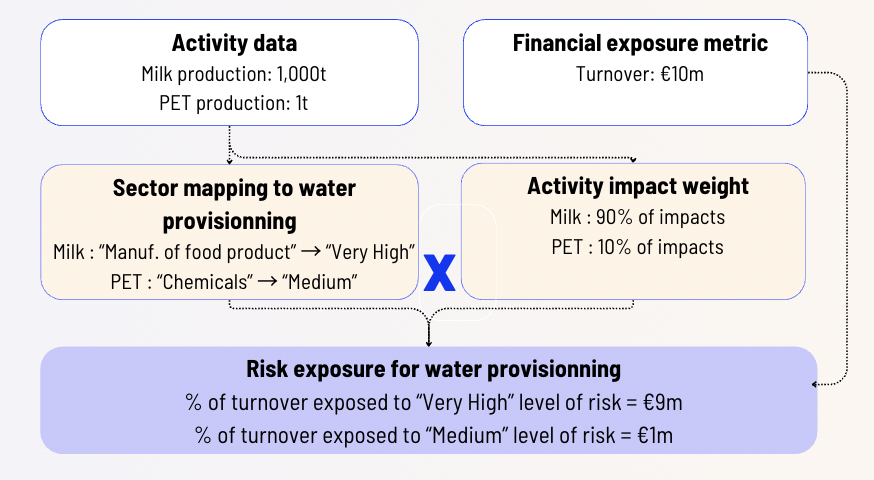

Zooming on point 3: how exposure analysis works on Darwin

Users first define a financial metric (e.g., revenue for a company, assets under management for a fund) and allocate it to entities (e.g. business units, products, assets). Granularity directly improves relevance.

For each entity, activities are characterised across direct operations and multiple tiers of the value chain. Risk exposure is differentiated by scope, a key element for robust analysis.

Activities are assessed using product-level and monetary data. 2 core operations are applied:

Sectoral mapping to derive impact and dependency materiality scores (ENCORE),

Activity weighting based on impacts, as a proxy for their “scale of interaction” with nature.

From exposure to action (PwC perspective)

Once net nature risks are identified, the objective goes beyond reporting to focus on action and decision-making:

prioritise nature risks by identifying the most exposed sites and activities.

build a biodiversity strategy aligned with corporate strategy and other environmental pillars (water, climate), avoiding trade-offs in line with the IPBES Nexus approach.

operationalise the strategy at site and activity level, engaging internal and external stakeholders.

The ultimate goal is to co-build roadmaps with stakeholders, turning risk insights into concrete transformation levers.

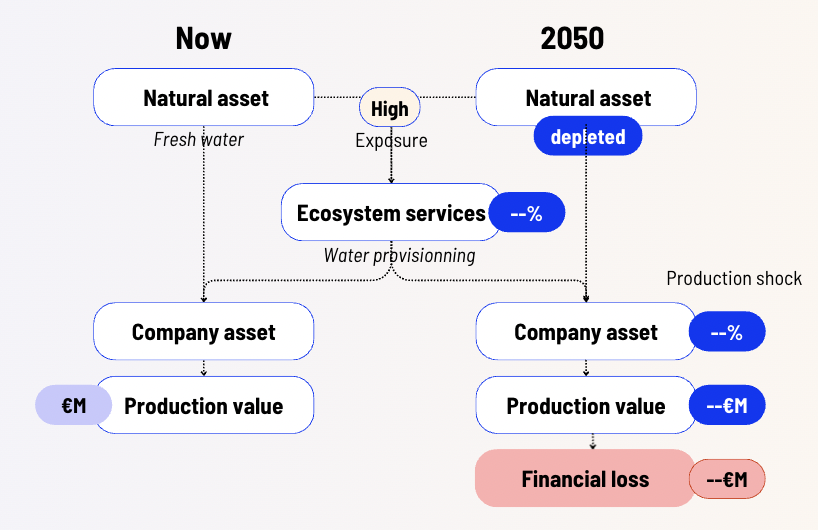

4. Looking ahead: how does nature risk evolve over time?

Exposure is not static. Nature risks evolve as ecosystems degrade, or recover. At Darwin, scenarios are used as a forward-looking lens. Exposure reflects sensitivity to nature risks. Scenarios estimate financial losses under ecosystem degradation pathways. Exposure is the transmission channel; scenarios quantify potential financial consequences.

The approach:

starts at the business asset level (e.g. factory, field, warehouse),

relies on 2050 nature scenarios for natural assets (water, soils, air, habitats, species) inline with recent central banks work, notably ECB,

links natural assets to business assets via ecosystem services they depend on,

translates ecosystem degradation into production shocks and, ultimately, financial losses.

Nature risk analysis is not about adding another ESG metric. It is about protecting (and potentially creating) enterprise value in a world where natural systems are under pressure. Moving beyond sites and beyond carbon is no longer optional; it is the foundation for resilient, future-proof business models. It also provides a decision-making framework to prioritize protection and restoration actions for natural assets, helping companies identify interventions that generate win–win outcomes for both ecosystems and business performance. At the end of the day, the new 2026 IPBES report underlines that biodiversity loss is a systemic risk threatening the economy, financial stability, and human wellbeing.